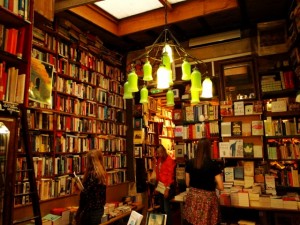

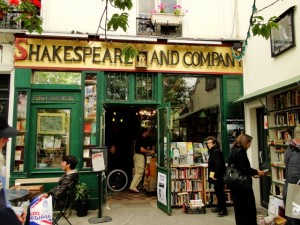

The windows are dusty in the corners of the grilles, the glass has rippled at the bottoms of the panes, and on this spring morning the leaves of a sprawling tree uncurl just outside. It is Sunday. The smell of coffee. The click of cameras. The bells of Notre Dame. Musty books are stacked two rows deep on wall after wall of crooked shelves in rooms full of old chairs with loose joints and thin cushions, rooms filled with the familiar reverberation of more English than you are used to hearing. Many people come to the rue de la Bûcherie to buy a stamped copy of Ulysses or The Sun Also Rises and take a picture in front of the famous storefront of Shakespeare & Company, the famed Paris English-language bookshop. In the reading rooms above the shop, where the books are not for sale, more steady clientele spend their Sundays. Shakespeare & Company is one of the few places to remain open in the face of the traditional French observation of the Sabbath.

While Shakespeare & Company is a tourist attraction — as it has been for a very long time — what it has been for even longer, although not by much, is a functioning bookshop providing English-language reading material and interaction for the people of Paris. It has changed locations, transferred owners, evolved its clientele, and weathered shifts in the publishing industry, but in the second story reading room with the windows open over the Seine, these changes seem distant and minute. It is, as it ever was, a place where enthusiastic people can read, write, learn, teach, work, and live. And on a morning when any number of people may be reading a book at their tablet on the streets below, its nice to know not everything is changing.

The shop on the rue de la Bûcherie is the reincarnation of the original Shakespeare & Company and is currently run by Sylvia Whitman, who took it over after her father George’s death in 2011. Many people fuse the Whitman bookshop with Sylvia Beach’s original Shakespeare & Company, which opened in the rue Dupuytren in 1919 before moving to its famous rue de l’Odéon location in 1922, and that might be by design. George Whitman is remembered as an eccentric character and the blending of the stores in literary lore fits Whitman’s personality. He was reported to also proliferate the idea that he was a descendant of the poet Walt Whitman. And while both shops have played a defining part in the world of literature, it is important to appreciate them separately.

In 1951, George Whitman opened a bookshop called La Mistral at the rue de la Bûcherie location. As an English-speaking bookseller it is no wonder he met the legendary Sylvia Beach. Whitman must have made an impression, because before she died Beach bequeathed the rights to the name ‘Shakespeare & Company’ to the young man — rights that he exercised in 1964, two years after Sylvia Beach died in Paris at age 75. George Whitman renamed La Mistral after the Odéon store and Shakespeare & Company was reborn. While there is certainly a correlation between the two shops, they never operated at the same time and supported different circles.

In 1951, George Whitman opened a bookshop called La Mistral at the rue de la Bûcherie location. As an English-speaking bookseller it is no wonder he met the legendary Sylvia Beach. Whitman must have made an impression, because before she died Beach bequeathed the rights to the name ‘Shakespeare & Company’ to the young man — rights that he exercised in 1964, two years after Sylvia Beach died in Paris at age 75. George Whitman renamed La Mistral after the Odéon store and Shakespeare & Company was reborn. While there is certainly a correlation between the two shops, they never operated at the same time and supported different circles.

Having traveled extensively throughout her upbringing, Sylvia Beach was drawn back to Paris around the end of the First World War. She had lived in the French capital with her parents from 1902 to 1905 and returned more than 10 years later to study contemporary French literature. One of the places she frequented was La Maison des Amis des Livres, a bookshop on the Left Bank run by a young French woman named Adrienne Monnier. Beach would make lifelong ties at the store, gaining friends in clients like Andre Gide, Paul Valery, and Jules Romain, as well as a lifelong companion in Monnier. Inspired by Monnier’s work to expose readers to new and innovative writing, Beach opened her own shop with the bit of savings she had, taking advantage of the cheap Parisian rent. What Monnier did with French writers, Sylvia began doing with English and American authors.

The story of Shakespeare & Company in the 1920s and 1930s is a fascinating story of the ascension of many young artists from lowly book borrowers to respected thinkers. Beach acted as secretary, mail sorter, moneylender, reading guide, and den mother to many of the century’s best minds. Most famous for her backing of James Joyce and as publisher of his Ulysses, Beach also supported many others such as Ezra Pound, T S Eliot, Thornton Wilder, George Antheil, Robert McAlmon, and Ernest Hemingway. Arguably the most central figure in the expatiate community in Paris, Beach watched fame come and go for the artists of this generation and slowly, especially because of her role as the publisher of Ulysses, began to see her own renown grow to the point where her store was a mainstay on the American tourist circuit. Beach lived modestly and put any profits back into the store (or into the always waiting hands of Joyce). She created such a loyal following that, when the depression hit, her French friends, authors Andre Gide and Jules Romains, organized a donation organization to keep the store afloat, and after the German occupation and WWII, according to Beach, Hemingway attempted to personally “liberate” the shop in uniform. Despite this attempt, the store, which sold its last books in 1941, never reopened. Beach was almost 60 years old by the time the war ended, and after the strain of keeping the store in business during the depression, not to mention the hardships she remembered from opening the first time, the idea of continuing Shakespeare & Company was not one she was enthralled with. She stayed on in Paris and played an active and influential part in the literary community, and although she no longer had the bookshop, she continued to support young artists as they came to the city.

Where Beach offered support, advice, free books, and a helping hand to the young artists of the 1920s and 1930s, Whitman took it one step further. He referred to the store as “a socialist utopia masquerading as a bookshop,” where people could come to find a warm bed, a little bit of food, and good conversation all for a few hours work. Over the years many visitors — ‘tumbleweeds’ as they were called — have stayed in the Whitman bookstore, with their numbers estimated in the tens of thousands. While their responsibilities have evolved over the decades, they are still accountable for a few hours of work and the reading of one book each day. The casual visitor can expect to find five or six ‘tumbleweeds’ roaming the stacks or lost in thought, albeit always eager to help locate the right book. The feeling of community among the staff, the tumbleweeds, and the patrons is one that still persists. As the experience of reading goes online, where people can buy books from the comfort of their own home and discussion groups are a click away, the environment at Shakespeare & Company is changing from unique to endangered.

But, while the proliferation of this environment is in trouble, Shakespeare & Company is continuing to spread its branches. Although their occurrences have been infrequent, the bookshop has worked hard on a few projects that have widened the scope of their influence. The Paris Magazine, called “The poor man’s Paris Review,” by George Whitman, is the store’s very own literary magazine, although only four issues of it have been produced since its inception in 1967. First published in a year when Shakespeare & Company was shut down due to licensing issues, the inaugural issue of The Paris Magazine had a formidable list of contributors, headlined by Jean-Paul Sartre, Marguerite Duras, Allen Ginsberg, and Lawrence Durrell. The most recent issue, published in June of 2010 under the editorial stewardship of Fatema Ahmed, included new work by Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Michel Houellebecq. The contributions are top notch and the magazine is much more than simply a product of tumbleweeds’ free time. A vital exhibition of the state of the literary world, past and present, The Paris Magazine proves Shakespeare & Company still has a beat on what we should be reading, writing, and thinking.

But, while the proliferation of this environment is in trouble, Shakespeare & Company is continuing to spread its branches. Although their occurrences have been infrequent, the bookshop has worked hard on a few projects that have widened the scope of their influence. The Paris Magazine, called “The poor man’s Paris Review,” by George Whitman, is the store’s very own literary magazine, although only four issues of it have been produced since its inception in 1967. First published in a year when Shakespeare & Company was shut down due to licensing issues, the inaugural issue of The Paris Magazine had a formidable list of contributors, headlined by Jean-Paul Sartre, Marguerite Duras, Allen Ginsberg, and Lawrence Durrell. The most recent issue, published in June of 2010 under the editorial stewardship of Fatema Ahmed, included new work by Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Michel Houellebecq. The contributions are top notch and the magazine is much more than simply a product of tumbleweeds’ free time. A vital exhibition of the state of the literary world, past and present, The Paris Magazine proves Shakespeare & Company still has a beat on what we should be reading, writing, and thinking.

What makes the magazine so good is the keen recognition of talent that its staff possesses. That same search for quality work has been applied to Festival & Co., their literary festival, and The Paris Literary Prize. Although Festival & Co., like the shop’s literary magazine before it, has come to be infrequent, The Paris Literary Prize is in full swing. The prize is given to the best unpublished novella submitted to the competition and is accompanied by a generous award. Given in the spring, this year’s winner was C. E. Smith for “Body Electric,” which has subsequently been published by the bookshop in collaboration with The Paris Review. The bookshop is also excitedly working on project that will tell George Whitman’s story and provide a follow-up to Sylvia Beach’s memoir, eponymously titled Shakespeare & Company, and reinforcing the history of the shop, due out the beginning of next year.

Contributing even more vitally to the Paris literary scene, and world culture at large, are the seemingly constant readings offered by the shop. In the spirit of Sylvia Beach’s readings in the rue de l’Odéon that once featured James Joyce, Andre Gide, and Ernest Hemingway, the great writers and artists of the moment seem to always make time for an appearance at the bookshop on their way through Paris. Charles Simic, Saul Williams, Rachel Kushner, and Barbara Kingsolver all appeared to give readings, talks, or performances this spring.

But what draws these people to the slouching steps of the bookshop, where the leather seat cushions are cracked and the narrow aisles crowded? In his essay, “Approaches to Distress,” translated from the French by George Miller and published in the most recent issue of The Paris Magazine, Michel Houellebecq attempts to define the ever-evolving disposition of the modern world. While the suppositions in the essay are far-reaching and perhaps more encompassing than an article on a small bookshop deserves, it is wholly unsurprising that it appeared in The Paris Magazine, as the bookshop itself fits right into Houellebecq’s theories. Although he tells the story of the arts in the modern world falling prey to the bland uniformity of the information age and the anxiety that it causes, literature is immune. This is because literature, as Houellebcq writes, “can deny itself, destroy itself, declare itself impossible without ceasing to be itself. It resists all…deconstructions.” In a time when “the physical world is [being] replaced by its digital image,” literature remains unscathed. Even though people buy e-readers and publish books online, Shakespeare & Company shelves remain stocked.

In contrast to today’s overflowing sidewalks in cities around the world, Houellebecq observes that as people “reach the cathedral district, the historic centre of the city…at once their pace slows.” Nestled in the shadow of Notre Dame, often their pace slows at the door of Shakespeare & Company, where a quick step inside allows a temporary respite from the rapid exchange of information happening outside, whether it was on your phone, in your office, or in the supermarket. That pace slows even further in the reading rooms upstairs, as patrons come and go below you and people flow by outside in the never ending throng, because “the book [is] a hardy point of resistance” to this ever-quickening pace.

You can still walk into the door of Shakespeare & Company, through the insulating velvet curtain in the winter months, to find an endangered atmosphere. Books are bought on recommendation and perception, not pushed by sales figures or because of their cost-to-benefit ratio. It is not a tourist trap, a cultural oddity, or a sideshow, as one might expect an independent bookstore to be in the age of Amazon. It is simply a store going about its business as usual, helping people in the ways it always has, selling books, and loaning beds. The history is in the pages on the shelves, the reputations of great artists and writers discussed in conversation, but it is the excitement for the future that is in the air. The bookshop, and the institution it upholds, is founded on its literature, and as Houellebecq comfortingly declares, “literature in the past has often been able to outstrip the real world; it has nothing to fear from virtual worlds.” And regardless of the time that has passed since Beach first conceived of the shop, its history still resonates — a foundation that is sure to survive long in to the future.

http://www.shakespeareandcompany.com/

Originally published in 2013

2 comments

Loved this article. So well written. Made me feel as if I was there or rather made me wish I was there. Books are so much a part of my life, but I can only dream or read articles like Mr. Callahan’s and live vicariously.