by Charles Maynard

Robert Frost, four time winner of the Pulitzer Prize, is said by some to have been the most widely read and continually anthologized American poet of the Twentieth Century. He won Pulitzers for New Hampshire (1923), Collected Poems (1930), A Further Range (1936), and A Witness Tree (1942). No other American poet has received that number of Pulitzer Prizes for their poetry or received such a high number of accolades from universities and foundations. When T.S. Eliot introduced Robert Frost to an English audience in 1957, he said of him, “Mr. Frost is one of the good poets, and I might say, perhaps the most eminent, the most distinguished, . . . Anglo-American poet now living.” It has been over four decades since his death in 1963 at age 89, and Robert Frost remains one of America’s leading 20th-Century poets.

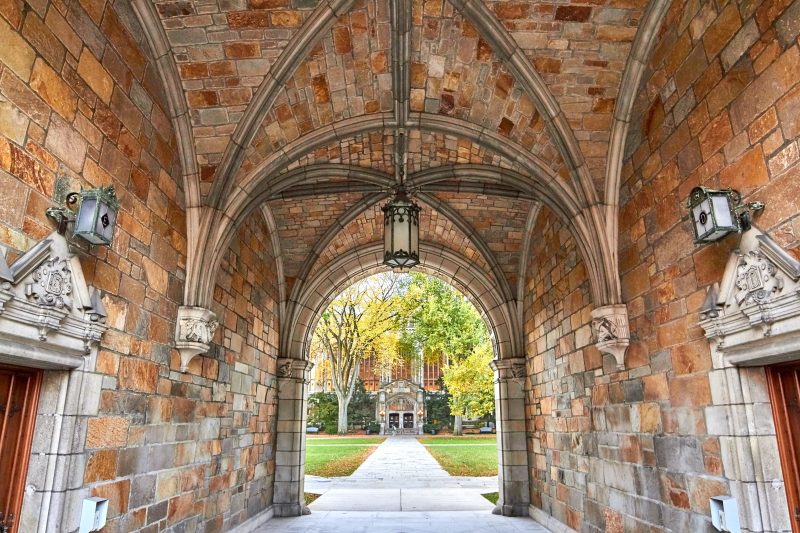

Although Frost is most often associated with the New England region, it is also known that he had deep and abiding associations with Ann Arbor and the University of Michigan. “I like Michigan people and I like Michigan,” he once wrote to a friend. In 1921 he accepted a $5,000 fellowship and became the University’s first Poet-in-Residence. After a brief return to New England in 1923, he came back to Michigan again for two years beginning in 1924 after receiving an appointment with the title Fellow in Letters. Frost had no official teaching obligations during his tenure at the University of Michigan and was fond of referring to himself as “Michigan’s idle fellow.” As he described it, his role was “to do my work and radiate poetic atmosphere for the University.” In fact, however, he’d never been busier. During his stay in Ann Arbor, Frost was in constant motion attending receptions, lecturing, and meeting with student groups. He also helped arrange a series of poetry readings by some outstanding American poets including Carl Sandburg, Louis Untermeyer, and Amy Lowell.

In the 1920s Frost was to become a well-known figure in Southeast Michigan and his activities received extensive media coverage. A local drug store in downtown Ann Arbor even created an ice cream treat in his name. This frozen dairy dessert was dipped in milk chocolate and marketed as Frost-Bite. Not to be outdone, a nearby bookstore promoted Frost’s writings as Frost-Bark Very Little Worse than his Bite.

Frost himself was inclined to down-play this notoriety. When the President of the Univesity, Marion Burton, suggested to Frost that he was as popular as the celebrated football coach, Hurry-up Yost, Frost responded by proposing that they test the soundness of this idea by scheduling a poetry reading that would coincide with an upcoming football match. He then cautioned President Burton if you come to my poetry reading, you will be the only one there, because I shall be at the football game.

During his years in Michigan Robert Frost accomplished some of his finest writing. He was most easily able to conjure up his creative spirit when he could manage to find time for cultivated leisure and spacious reflection. One such occasion was in the late winter of 1926 when his wife Elinor had returned to New England to attend to their daughter Marjorie who had been hospitalized with pneumonia. Afflicted himself with the flu and feeling somewhat abandoned, Frost withdrew to the comfort and solace of his handsome Greek revival house on Pontiac Trail. There he tried to ward off the late winter chill, along with his low spirits, by kindling a roaring fireplace blaze with branches from a fallen black walnut tree, lazing on the couch, and devoting himself to writing for three undisturbed and restful days. One gratifying result of this retreat was a delicate and poignant poem entitled Spring Pools. In a conversation with Edward Latham some years later, Frost recalled the circumstance: “I lived out on Pontiac Road then. One night I sat alone by my open fireplace and wrote Spring Pools. It was a very pleasant experience, and I remember it clearly, although I don’t remember the writing of many of my other poems.”

Spring Pools captures the natural rhythms of seasons in transition and the astonishing transformation of the flowering waters to the dark foliage of the summer woods.

SPRING POOLS

These pools that, though in forests, still reflect

The total sky almost without defect,

And like the flowers beside them, chill and shiver,

Will like the flowers beside them soon be gone,

And yet not out by any brook or river,

But up by roots to bring dark foliage on.

The trees that have it in their pent-up buds

To darken nature and be summer woods—

Let them think twice before they use their powers

To blot out and drink up and sweep away

These flowery waters and these watery flowers

From snow that melted only yesterday.

During this time in Michigan, Frost wrote another widely admired poem entitled, Acquainted with the Night. This work is considered by many to be a master-creation of American literature. While it is widely accepted that the poem was written during his tenure at the University of Michigan, there remains an ongoing dispute about whether the “luminary clock against the sky” referenced in the last lines of the poem refers to the Burton Memorial clock tower located in the central part of the University campus. Some have rejected this popular local legend as being in disagreement with a key historical fact. They point out that while the poem was published as part of the collection West-Running Brook in 1928, the Burton Tower was not dedicated until nearly ten years later in December of 1936.

There is, however, additional evidence to be weighed. First, it does seem likely that Frost was inspired to write this poem during one of his habitual late night walks around the city streets of Ann Arbor. It was well known that he suffered from insomnia. A former student of Frost recalls that the poet had a habit of taking long, meandering late night strolls around the city. There was even talk that during one such trek Frost was stopped and questioned by the police who thought him to be of suspicious character.

There is convincing evidence that the luminary clock mentioned in the poem refers to another Ann Arbor landmark. Peter Stanlis, a prominent literary scholar and friend of Robert Frost, has said he had a conversation with the poet in which Frost told him that the one luminary clock against the sky was, in fact, the Victorian clock tower on the Washtenaw County Court House in Ann Arbor. According to a University of Michigan alumnus who lived in Ann Arbor at that time, in starting out from his house on Pontiac Trail, Frost would have walked over the viaduct by the train station and up Division Street. Off to his right he would have seen the clock tower of the old courthouse.

Whatever the origins of its stirring imagery, this meditative poem captures the state of liminal consciousness that can overcome us in the solitude of the late night hour.

ACQUAINTED WITH THE NIGHT

I have been one acquainted with the night.

I have walked out in rain — and back in rain.

I have outwalked the furthest city light.

I have looked down the saddest city lane.

I have passed by the watchman on his beat

And dropped my eyes, unwilling to explain.

I have stood still and stopped the sound of feet

When far away an interrupted cry

Came over houses from another street,

But not to call me back or say good-bye;

And further still at an unearthly height,

O luminary clock against the sky

Proclaimed the time was neither wrong nor right.

I have been one acquainted with the night.

While some see this pensive verse as conveying a rather foreboding sense of solitude, others have suggested a less doleful interpretation. One can imagine Frost, during one of his characteristic bouts of sleeplessness, ambling along the shadowy late-night streets of Ann Arbor seeking to assuage his restlessness spirit. As he glances up at the luminary clock against the sky, he has a sense of timeless belonging of the inexorable flow of time revealed at an unearthly height. He experiences an eternal and ceaseless sense of time that is neither wrong nor right– a sense of time that joins the isolated self within a broader context of belonging.

Walking in these hours of darkness, Frost meets up with a night watchman. Perhaps possessive of this gift of solitude, he elects to ignore the watchman on his beat unwilling to explain. It seems plausible that he hoped to safeguard those precious moments of compelling melancholy and timeless connectedness. Perhaps Frost is affirming T.S. Eliot’s view as expressed in East Coker, that in the darkness shall be light, and the stillness the dancing.

Whatever the interpretation given to Frost’s poems written in these Michigan years, it is clear that Ann Arbor was a place where his imagination and his creative spirit soared.

Charles Maynard is a freelance writer living in Michigan. This article is based on a work in progress tentatively titled Michigan Reflections, a literary anthology of celebrated authors who have traveled to Michigan or called it their home.