By mid-morning on this dreary gray Sunday, crowds of people dressed in shorts and sporting baseball caps, are bustling in and out of the many baseball memorabilia shops lining Main Street. The brick facades bear names like Mickey’s Place, Seventh Inning Stretch, and National Pastime, and they sell everything associated with the game, from baseball apparel, cards, equipment, and autographed memorabilia to baseball art, medals, statues, and pricey collectibles.

Named after William Cooper, a wealthy land speculator, county judge, and father of novelist James Fenimore Cooper, the village of Cooperstown on Lake Otsego in central New York is a shrine to pure Americana, the home to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

“When we arrived in 1973, Cooperstown was a struggling small town with small businesses—a local bank, grocery stores, a sewing shop, hardware stores, and an old hotel called The Otesaga,” says my friend Tom Conroy, a New York photographer and history buff. “It had a historic sense of place, but baseball has overwhelmed the town’s past. It brought fame and tourists and celebrity baseball players with their multi-million dollar salaries.”

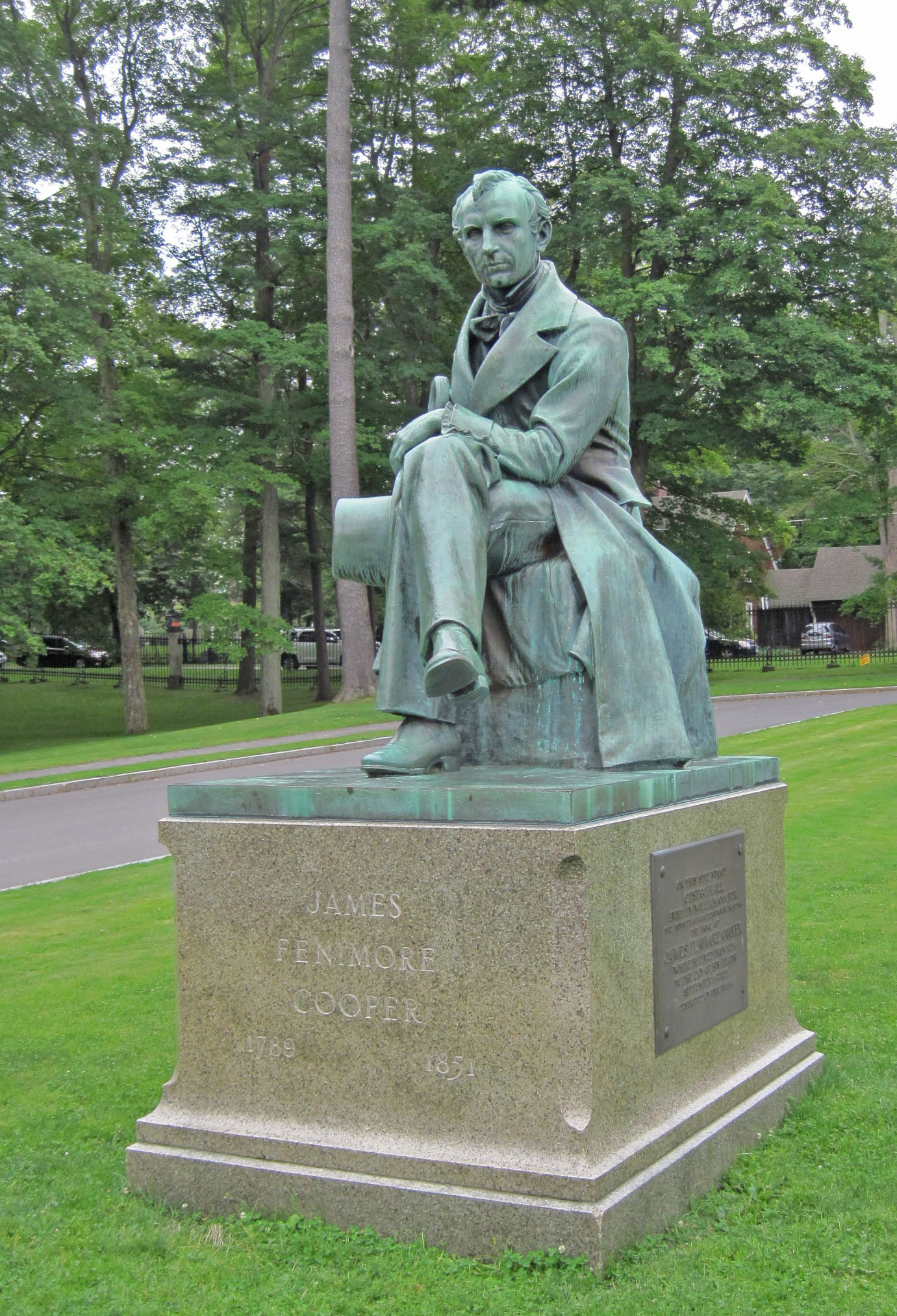

There’s scarcely a trace of the historic village’s affiliation with the famed novelist, except the bronze statue of him seated on a rock in the Cooper Grounds or Park. Unveiled on August 29, 1940, the statue now wears a patina of green from oxidation over the decades. With one leg folded over the other, Cooper sits snugly wrapped in a massive frock coat, holding a top hat and cane in his right hand—the epitome of the aristocratic gentleman that he was.

On the opposite side of the little park stands a modern multi-storied stone building that houses the Hall of Fame’s research library. The juxtaposition of the statue and library represents Cooperstown’s transformation and metaphorically Cooper’s—his search for identity and connection to the ever changing frontier village two centuries ago.

Born in Burlington, New Jersey on September 15, 1789, James, the youngest son, was but a year old when his father moved the family to the backcountry village on Lake Otsego. The young boy was raised in the rural luxury of the judge’s “Manor House.” Built in 1788 of beaded wood siding on the present site of Cooper Park, the two-story home on the village’s Main Street had a commanding view of the lake.

By Cooper’s time, the line of settlement had moved westward beyond the village. He never saw the frontier; yet, his five-part series, The Leatherstocking Tales, helped create a mythical West that transformed the reality of life on the frontier and launched his career as the first self-supporting American writer. In his greatest character, Natty Bumppo, he created the archetypical western hero in American fiction, whose literary descendants range from Mark Twain’s renegade hero Huck Finn to the hunters and scouts in Erastus Beadle’s (another New Yorker) dime novels and the cowboys in Hollywood’s movies.

His inspiration to write was rooted in a fervid imagination and his boyhood memories of an earlier Cooperstown and his father’s pivotal role in its settlement. James and his older brothers roamed and explored the “interminable woods,” sometimes with reckless abandon according to his sister Hannah. Although he seldom encountered Indians, he met and listened to the stories of white hunters and Revolutionary war veterans and observed wagon trains of settlers passing through the village on their way west.

Their stories and his childhood memories became the marrow of his craft. Real people served as models for his leading characters. Natty Bumppo was based largely on David Shipman, an old hunter dressed in tanned deerskin who often visited the Manor to offer game at the Judge’s back door. Chingachgook, the Indian character in Cooper’s bestselling The Pioneers (1823) and The Last of the Mohicans (1826), was based on a wandering Mohican basket-maker and hunter named Captain John. The Prairie (1827), The Pathfinder (1840), and The Deerslayer (1841) followed.

By the time Cooper began writing The Pioneers, Cooperstown and Otsego County had become a settled, crowded rural community. The town was plagued by unrestrained development, land clearings, poor harvests, bankruptcies and foreclosures, political factionalism, and social unrest. It was no longer a frontier village ripe with promise.

Each spring flocks of migrating passenger pigeons were wantonly shot down leaving the ground littered with dead and dying birds. Clap nets and bait traps were set around the edges of bird roosts and nesting colonies to provide feathers for the hat-making trade. Great schools of bass in Lake Otsego were hauled in with dragnets, and much of the forest, including economically useful trees like the sugar maple, were razed by the woodchopper’s axe.

Set on the Otsego frontier in 1793, The Pioneers reflects the ecological problems that plagued the troubled community during Cooper’s time. The novel’s central characters are Judge Marmaduke Temple, modeled on Cooper’s father, and the aging hunter Natty Bumppo. Cramped by the ever-retreating forest, Natty has been reduced to poaching game on private property. His conviction for the unlawful offense leads to his memorable exchange with the judge about the changing environmental conditions.

Judge Temple tells Natty that laws can be passed that will spare the maple. Natty argues that the real problem is Temple’s lucrative profit from land sales. “Put an ind, Judge, to your clearings….Use, but don’t waste. Wasn’t the woods made for the beasts and birds to harbour in?” The hunter is the novelist’s alter ego. He gives voice to Cooper’s belief that his father’s profits as a frontier land developer had helped tie the Otsego country commercially to a market economy that sees the trees and animals only as exploitable resources.

The Fenimore Art Museum now stands on the site of James Fenimore Cooper’s 150-acre farm. Located off Highway 80 inside a 1930s neo-Georgian brick mansion overlooking Otsego Lake, it houses some of the nation’s finest examples of American landscape paintings and American folk and Indian art. It also has a room devoted to Cooper memorabilia, including family portraits, and paintings based on his novels.

“The Cooper name has been tied to the Otsego Lake region for more than ten generations,” reads the museum text panel. “It is here that a special bond united a family with the land, prompting a vision that inspired a great American literary tradition. Lake Otsego and its surrounding landscape continue to be animated by the same spirit that enamored the Cooper family.”

The lake was special to Cooper, and it has not changed much since his time: still limpid blue and absolutely calm with scarcely a ripple — a ‘glimmerglass’ to borrow from him. A patchwork of open fields, meadows, and heavily forested ridgelines flow out from it. In Cooper’s time, much of the forest had already been cleared. There’s a rural serenity here, a natural beauty, but it is being crowded out by the resort motels, inns, and private residences that overlook the lake. The din of the woodchopper’s ax has been stilled, replaced by the whir of road traffic. It’s a different time and place.

By early afternoon, Tom and I are again picking our way through crowded Main Street. It’s a scene reminiscent of a Norman Rockwell painting. Three brothers, dressed in recently purchased baseball outfits, proudly cling to one another arm in arm. A father, holding his small daughter’s hand, with his nose pressed against a storefront window, stares at the #14 jersey of his boyhood idol Pete Rose.

Baseball has cast an incurable spell and within minutes both of us are sitting on metal bleacher benches at Doubleday Field watching America’s favorite pastime. The 1939 brick grandstand, the umpires dressed in their thick black padding, and a field without lights are throwbacks to an earlier, perhaps more innocent time when every kid our age played ball.

Oblivious to Cooper, we retrace our steps and pass the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum at 26 Main Street. American flags are draped over the second story balustrades of the stately red brick building.

We return to Cooper Park. Looking at the Hall of Fame research library and Cooper’s statue, I ask Tom what he thinks about Cooperstown and its association with its most significant family. “James Fenimore Cooper and his dad don’t have much representation in the town today. It survived by reinventing itself,” he says. “Cooperstown didn’t suffer the fate of most 19th century New York small towns; it isn’t derelict, obsolete; bypassed by history. Instead, it’s alive and thriving.”

“If you want to really do Cooperstown justice you should tour the Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. A lot of ink has been spilled over the national pastime during the past two hundred years, some of which qualifies as literature. The Bart Giamatti Memorial library is a Mecca for baseball statisticians and researchers. In addition to being inveterate nostalgics, baseball fans are literary travelers too.”

And therein lies the rub. Cooper was not a great writer. He wrote hastily, without deliberation or making revisions in a style that was excessive, often unrealistic, and overly sentimental. However, as America’s first widely read novelist, he gave voice to one of the seminal themes in the nation’s history, one that was being played out in Otsego County and all along the advancing frontier: the conflict between nature and civilization. Alarmed by the disappearance of the great forests, its wildlife, the Indians and hunters, he hoped that the onrush of settlement could be reined in. That, of course, did not happen during his lifetime or in The Leatherstocking Tales.

“Cooper,” writes the historian William H. Goetzmann, “was the great novelist of changing America, and at the heart of his work stands the ambivalence and paradox that are central to the American historical experience.”

During a prolific career that spanned three decades before his death in Cooperstown on September 14, 1851, James Fenimore Cooper wrote thirty-four novels, the first history of Cooperstown, and numerous commentaries on politics and society. His literary contributions mattered.

Why then is he, along with his father William, the town’s founder and developer, only vaguely remembered? A room in Cooperstown’s museum and several statutes in the parks seems hardly fitting.

Neither the town’s reincarnation as America’s capitol of baseball, beginning in 1939, nor its development as a major tourist hub are adequate explanations. The town’s association with the Cooper family vanished much earlier. Judge William Cooper’s Manor House, for instance, burned down in 1812. An arsonist gutted James Cooper’s beloved Fenimore House, the site of the Fenimore Art Museum, in 1823. Fire also destroyed Otsego Hall in 1853, where Cooper had lived from 1834 until his death and the Chalet Farm House, his retreat, in 1958. None of the homes have been rebuilt.

The only building still standing in Cooperstown closely linked to James Fenimore Cooper is Christ Episcopal Church. “Cooper oversaw and bankrolled a major remodel of the church in 1840,” Tom tells me. “The Gothic Revival features that you see—the pointed stone windows, the brick buttresses, and the transept—were part of that effort. They are a testament to his sense of responsibility.”

We walk into the churchyard. Long narrow shadows from the rows of headstones slice through the sunlit grass. The family plot, which Judge Cooper purchased, is set apart from the rest of the gravesites. Here, Cooper and his wife Susan Augusta are buried side by side in simple slab tombs marked with crosses, along with his father, his mother Elizabeth Fenimore, his brothers, sisters, children, and family descendants.

Cooper has not been forgotten here, but the setting has changed greatly since his time with parish additions and the grid of paved streets and modern residences surrounding the church grounds. It’s too picturesque, too manicured and meticulously cared for. A better time to come is during the off-season when winter snows blanket the churchyard in stillness.

The place where I felt a tangible connection to Cooper’s vanished world was the Leatherstocking Monument located in Lakewood Cemetery. Erected in 1860, the weathered white Italian marble obelisk commemorates Cooper and his famous hero, Natty Bumppo, who stands atop it with long rifle in hand and his faithful dog Hector at his feet.

In the brooding silence shut off by a forest thick with hardwoods, a sense of the past, both imagined and real, lingers. The fictional and probably the real Natty Bumppo (David Shipman) hunted here and built their huts to store pelts and gear. The road below is the historic route once used by travelers coming into the frontier village and by Natty in the opening scene of The Pioneers.

* * * *

Few people read Cooper today. He is forgotten, irrelevant; a literary ghost who has vanished from our cultural memory. There is little left of his physical world in Cooperstown or a sense of place associated with him.

This is unfortunate because his writings were remarkably ahead of their time and are relevant now. He was the first American novelist to voice an environmental viewpoint. He tried to warn his countrymen that the land’s resources are not inexhaustible, that natural beauty, wilderness, wild creatures and plants should be preserved, and that failure to heed nature’s warnings might spell their own destruction.

*

For more information on James Fenimore Cooper and the legacy he left in Cooperstown and beyond, read our interview with the author, Victor Walsh, and join us as we take a look “Behind the Article.”