The moment I saw him I knew he was the man I would marry. A twenty-minute conversation changed my life; in those first moments we both said, “I’ve always wanted to drive across America like Jack Kerouac.”

Five years later, with a diamond ring on my index finger and a mop haired man in tow, we were leaving for the United States, September 1. The USA was the first stop in a two-year journey across the world. We were doing what we dreamed of in that first moment of falling in love.

While I am enamored of On The Road, Kerouac’s most famous novel, I am more partial to the Dharma Bums. It’s about the spiritual side of traveling, encountering God in the footsteps of a mountain, praying in the woods and finding a place in the universe.

In the Dharma Bums, Kerouac envisaged a “rucksack revolution” with “thousands or even millions of young Americans wandering around with rucksacks, going up to mountains to pray, making children laugh and old men glad, making young girls happy and old girls happier, all of ‘em Zen Lunatics who go about writing poems that happen to appear in their heads for no reason and also by being kind and also by strange unexpected acts keep giving visions of eternal freedom to everybody and to all living creatures…”

With this vision in my head, and a rucksack on my back, we arrived in Los Angeles’ Union Station, an art deco sprawl of old wooden seats, a hundred people waiting for links out of the city, waiting for trains to take them elsewhere. We picked up our car from the station for a month of driving around the West Coast of America.

The plan was to take Highway One from LA to San Francisco, but we were not driving in accordance with some map made by an ardent beat fan. We did not want to emulate the same journeys as our heroes but to create new ones.

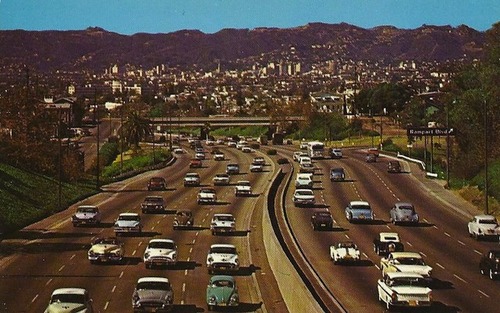

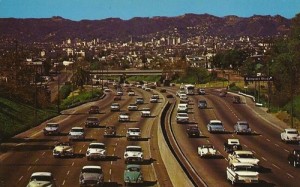

Sprinting out of LA in our tiny car, we turned off the major highway and onto the coastal route. Kerouac captured the slick city perfectly; “The smog was heavy, my eyes were weeping from it, the sun was hot, the air stank, a regular hell is L.A.”

Through the ups and downs of the mountains we turned, heading towards the elusive ocean. At first a small blue spot through the hills until we descended to the same level of the ocean, joining the coast just past Oxnard. I kept repeating to Justin “This is what we came for,” as the ocean lay flat, a hundred meters from the road.

Highway One, the All-American Road, began in the 1930s but was officially named in 1964. A highway famed for beatniks and ingénues riding in red convertibles as their scarves fly off in the wind.

At lunch we stopped at Santa Barbara and ate stuffed crab sandwiches on the end of the pier. The September sun glared down, casting strong shadows on the locked up bikes next to aisles of palm trees, past the weatherboard shacks, where a fortuneteller’s signpost flopped in the still air. It felt good to be out of the city, far from the density of Los Angeles.

As we drove closer to the Montana del Oro campsite, it was as if a curtain of grey descended on the world, from the pure blue skies of the coast to another world of cloud and fog. A light rain spat on our car driving up through the gates to the campsite.

We parked the car, carting our rucksacks up the steep hill, returning for food. If the weather had been good, we would have seen endless cliff lines, but fog dragged across the horizon, so that only glimpses of cliff could be seen through patches of loose fog. In the distance, the last glimpse of a golden shaft of sunlight, then gone and grey once more.

We prayed in our small blue tent, silently feeling the enormity of the world pressing down against our miniscule bodies. Though I’m a Christian, I was profoundly influenced by Kerouac’s Buddhist vision of travel, of “getting nowhere and thereby learn”. And I was nowhere, invisible in the miles of fog up and down the cliff line, high on a hill without a soul except the warmth of my husband beside me.

He wrote, “[I wanted to] go off somewhere and find perfect solitude and look into the perfect emptiness of my mind and be completely neutral from any and all ideas. I intended to pray, too, as my only activity, pray for all living creatures; I saw it was the only decent activity left in the world.”

Inside the food box, a long forgotten wooden cupboard next to a picnic table nested a small bird.

The following day we ventured up Big Sur, the snakelike coastline that inspired Kerouac, Steinbeck and Henry Miller. But our five hour journey through roadwork had nothing of the romantic beatnik feel about it and everything of car sickness, windy roads and the tension of driving at twenty miles an hour.

We arrived at Fremont Peak State Park as far from peace as is possible.

The entrance to the park lay at the foothills of the Californian mountain range, past wooden farmer’s houses and uneven paling fences. The GPS indicated a six-mile vertical drive to the campsite at the top of the mountain. The engine grunted as I pushed the accelerator, forcing the small car reluctantly up the hill.

I’d looked at it on Google Maps, but the flat lines of a map can never capture the beauty of a place. Maps only hint at the possibility of a place, several lines together indicating a steep ridge, the blue expanse of the ocean. A number for the height, a curved line to show bands of altitude. Maps are the statistics of natural beauty.

The road twisted like a snake through the landscape, dropping off in vertical slopes covered in pine trees. As I got higher, the altitude revealed the Californian landscape stretching on to the sea. Without barriers the road became perilous; a wrong turn could result in a significant accident.

At the top we stopped and placed $20 in a yellow envelope for a campsite. I pitched my tent in a grove of trees, glints of sunlight peeking through the oak leaves. The great Californian expanse was hidden by the grove; I longed to glimpse that view which had accompanied me on the drive.

At sunset I began climbing to the summit, as the sky ran purple then blue then red, centering around the yellow sun falling on the horizon. Above the silhouettes of pine trees, the endless clouds rolling across the landscape, until the clouds themselves became the ocean and wafted in and out along green passes of fields and Salinas.

A broken staircase led upwards, the path spiraling in rocky circles. A purple sky descended on the nearby mobile phone tower creating an alien landscape. Fields of pale grass whispered in shifting lines to the silhouette of a solitary grand oak.

I shared the same feeling of aloneness that Kerouac expressed, “What does it mean that I am in this endless universe, thinking that I’m a man sitting under the stars on the terrace of the earth, but actually empty and awake throughout the emptiness and awakedness of everything.”

As a photographer, you know that there are some moments that you are not going to be able to capture, no matter how hard you try. There are no filters to absorb beauty into the square pixels of a digital image. The best you can do is enjoy the moment, not regretting what you couldn’t take home. Because a photograph of the mind is recalled at will. I can still see those clouds making Fremont Peak no more than an island in the sky.

Months later I found out that John Steinbeck had camped in the same place in the 60s, and spoke the same things to his dog, Charley. I never stayed at Fremont Peak because of a literary celebrity worship trail; it was simply a convenient campsite.

Steinbeck wrote of Fremont Peak that “I remembered how once, in that part of youth that is deeply concerned with death, I wanted to be buried on this peak where without eyes I could see everything I knew and loved, for in those days there was no world beyond the mountains.”

Steinbeck and Kerouac shared that same love of travel, and travel in America. They both wrote two of the most influential books on the national travel consciousness. I can see the obsession; there are places in this nation that are uninhabited, far from the cities of noise, there are places where you feel like no one, that you are the last person on earth and all the world is yours.

The final day of our journey up the coast, we bailed on Highway One. We were tired; my husband didn’t want to drive any more on the endlessly winding roads. We wanted showers in San Francisco, and we wanted to get there quickly.

I have a friend back in Sydney, who would hate to be called an older woman but she was around San Francisco at the time of the beats, listening to poetry in the City Lights bookshop. She made me promise to go there; one of those inspirational places both a landmark and a bookstore, the type that bibliophiles like myself go mad in, rushing from one shelf to the next, exclaiming at every type of cover. There was a whole bookshelf dedicated to Kerouac, alongside reprinted versions of Ginsberg’s HOWL in their black and white covers. I couldn’t buy anything, not a single word of literature, for I had two years of travel ahead of me and not another space in my bag between gas stoves and wool socks.

Across the street was a beatnik museum, an odd collection of shambling memorabilia and dog-eared books. Souvenirs, a number of beatnik badges and books, and a friendly staff member who took a photo of us in front of the large painted mural of Jack Kerouac. It felt strange to remember these vagabond romanticists in a museum, and not in the mountains, running through nature with their rucksacks and notepads.

Down a thin Chinatown street in San Francisco was Jack Kerouac Alley, where poetic quotations of adventure lined the pedestrian only walkway. Standing on the street, I thought back to those moments when I felt smaller than the world, where the land stretched far into the ocean to become a perpetual line to eternity. These are the places where the literary memory lives on. Embellished gold in the concrete under my feet were the words of John Steinbeck, “The free exploring mind of the individual human is the most valuable thing in the world.”

*

For more from Kat Clay, check out our accompanying interview with the author and take a look “behind the article.”