The Quiet American by Graham Greene ought to be required reading for anyone planning a visit to Vietnam. For more than forty years, this prophetic portrait of the failing days of French colonial rule has been alternately praised and reviled by critics, but still stands as the definitive, though fictionalized account of the terrible confrontation between moral dissipation and dangerous naivete that plagued this tropical nation for so many decades. Vietnam has come a long way from those troubled times.’

The Quiet American by Graham Greene ought to be required reading for anyone planning a visit to Vietnam. For more than forty years, this prophetic portrait of the failing days of French colonial rule has been alternately praised and reviled by critics, but still stands as the definitive, though fictionalized account of the terrible confrontation between moral dissipation and dangerous naivete that plagued this tropical nation for so many decades. Vietnam has come a long way from those troubled times.

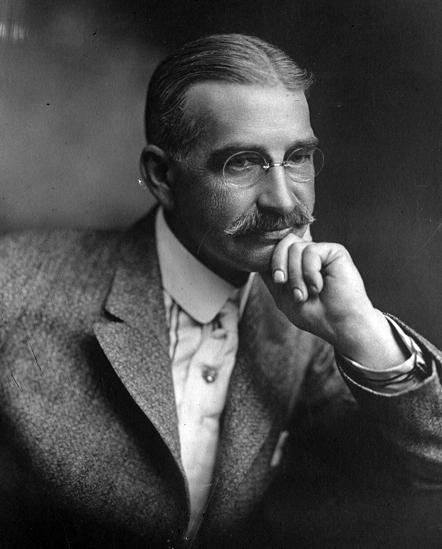

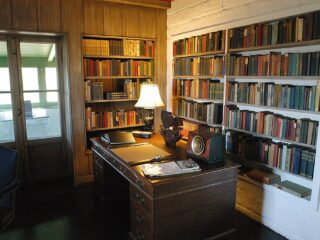

Since Graham Greene’s death in 1991 a plethora of biographies has emerged, each stressing the real world sources for much of what the author wrote, and each including old photographs of the places where he lived and drank and caroused. Given the intervening twenty years of war and twenty more of political isolation, it would come as no surprise to find that none of Greene’s old haunts in Vietnam are still standing. But not only are they still there, many of them have been restored to better than mint condition. Indeed, Vietnam today is full of astonishing contrasts to the opium-soaked, decadent world of Greene’s novel, and the irony of some of these contrasts can only be deliberate.

Taking yourself on a Graham Greene tour of Ho Chi Minh City, you should begin in the Rue Catinat, now called Dong Khoi. Though the name has changed, the street is impossible to miss. Where it reaches the Saigon River, the street is prominently marked by Catinat Fashions, an upmarket haberdasher housed in a beautifully restored French Colonial building and finished in cream stucco to match the even more sumptuously restored Majestic Hotel across the street. Greene stayed at the Majestic, preferring it to the Continental, the more popular journalist hangout, also on the Rue Catinat a few blocks inland.

Built in 1928, the Majestic Hotel offered opulence much closer to the life Greene enjoyed as a wealthy and famous novelist than to the seedy back-alley rooms inhabited by Tom Fowler, Greene”s protagonist in The Quiet American. Perhaps Greene liked the Majestic because here he was somewhat insulated from the dangers of the street. In the cozy central courtyard, lounging around the pool he could easily have imagined being in Nice or St. Tropez, and Greene was a born again Frenchman. The Majestic’s roof bar has a fine view both up and down the river where you can contemplate the strange flavors of Vietnam”s cultural melange from a safe height. Below, sampans share the waterway with high speed hydrofoils. After dark, above the dark tangle of bamboo scaffolding and corrugated iron shanties on the opposite bank, giant neon billboards advertising Heinekin, Phillips and AIWA seem to hang suspended. Icons of the re-instated corporate pantheon. Even more incongruous is the mariachi band on the Majestic”s open roof-deck wearing sombreros and black suits and playing Mexican swing for the tourists.

Greene lived in at least two places on the Rue Catinat and chose a third as the model for Fowler’s apartment in The Quiet American. He didn’t need to go far to find Fowler’s place. It is on the next corner in from the Majestic. A picture in Norman Sherry”s biography The Life of Graham Greene shows this building in pretty sorry shape, but now it is The Grand Hotel, a spotless edifice, more cream stucco and white marble punctuated with dark mahogany counters and liveried attendants. A little farther up the Rue Catinat is the Palais Cafe, where Fowler played quatre cent vingt-et-un with lieutenant Vigot of the Surete. This bar too has been renovated, but it is somewhat darker and livelier at night than the sedate hotels down the street. Greene also stayed for a time in an apartment a little farther up the Rue Catinat, at number 109. This building is now a modest hotel called the Mondial.

Last on this leg of the Greene tour is the Continental Hotel, for decades a gathering place for foreign journalists and a hotbed of political intrigue. The Continental was restored somewhat earlier than the other hotels on the Rue Catinat. It has a slightly more traditional Vietnamese feel than the distinctly French-influenced Majestic and Grand (The Continental is half the price). There is no outdoor bar at the Continental anymore, but indoors, crouched behind a Bombay Sapphire martini on the rattan furniture of the lobby bar, it is not difficult to imagine the author coming in to meet friends before dinner, or Fowler making an assignation with Pyle, the American secret agent.

Venturing farther afield, the contrasts between Vietnam then and nowbecome even more striking. For example, in The Quiet American Greene refers to a place he calls “The House of 500 Girls.” It was actually known as The Parc au Buffles by the French and was a three-sided complex catering to the darker side of old Saigon. That was then. Now in the center building where the casino used to be is an arts education center. Off to the left where there were once rooms for smoking opium is now a roller skating rink, Chuck Berry music blaring, hundreds of little wheels rumbling over wooden floors and young people still in school uniforms laughing with glee as they swirl around and around. On the right, replacing the brothel, is a ballet academy.

The Dakow bridge, where in The Quiet American Pyle gets murdered by the resistance for his misdeeds, is being replaced. The old bridge is already gone, though the new one is not yet constructed. Nearby another larger construction project is underway. The shanties that once lined the estuary approaching the Dakow bridge have been removed and in their place will be a concrete seawall promenade with grass and shade trees. Although the squalid canals of the old city are still very photogenic, even the people who live on them consider them an eyesore, and energetic programs are rapidly relocating their inhabitants to new housing projects in the south and cleaning up the water.

Many other buildings that Greene mentions are also still standing and easy to find. The central post office, the cathedral, the Banque Indo Chine (now the National Bank of Vietnam) and more are all still in beautiful condition and within walking distance of the Dong Khoi, the Rue Catinat.

Right now is a magical time in Vietnam. The crime rate is way down; prosperity is up and the whole nation seems to have its attention turned outward toward the rest of the world, poised to learn and to grow. Be advised though, the first American fast food franchise opened in Ho Chi Minh City in January of 1998. If you want to see Vietnam while its new charm is still fresh, now is the time.

More on the Web

Graham Greene

Greeneland the world of Graham Greene

Graham Greene

Personalized page with lots of info