Hiroshima is one of those words so laden with meaning, so heavy with history, that its mere mention, without elaboration or context, conjures a vivid story of victory and devastation. Most people can tell you in general terms what happened there. But if you don’t know Keiji Nakazawa’s Barefoot Gen, you don’t know half the story. This masterpiece of the manga form relates a semi-autobiographical account of Nakazawa’s experiences as a young boy growing up in Japan during and after the war. The elderly hibakusha—literally, “bomb-affected person” or a-bomb survivor—Nakazawa does not make many public appearances these days, but on a recent trip to Hiroshima on the occasion of the anniversary of the atomic bombing, I was lucky enough to sit in on a private event in which he reflected on his life, including his brilliant and moving manga series.

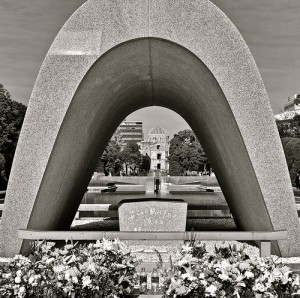

Before my audience with the man himself, I took the opportunity to visit some of Hiroshima’s most historical significant sites, places that figure prominently into the narrative of Barefoot Gen. To understand Nakazawa and his work, it is important to grapple with the physical layout of the city, including the iconic A-bomb Dome and Peace Memorial Museum, as well as the historical context of the bombing itself.

During the Second World War, aerial attacks against civilian populations for the deliberate purpose of damaging morale—of causing terror—became a central tactic of American warfare. Americans, of course, did not originate aerial bombing of civilian targets. During the 1930s, it was largely a reviled method of fascist forces. The United States declared its moral outrage, but by the end of World War II, with the help of the United Kingdom, had killed at least 800,000 and possibly more than one million people using this method. As one celebratory public-relations release issued by the United States Army Air Force put it, “For five flaming months [at the end of the war]… a thousand All-American planes and 20,000 American men brought homelessness, terror, and death to an arrogant foe, and left him practically a nomad in an almost cityless land.”

In early 1945, in the midst of extensive, ongoing firebombing raids, Hiroshima was singled out as a potential target for the soon to be operational atomic bomb. An empirical demonstration of the bomb’s power was a primary factor in the selection of Hiroshima as a target. The pure accident of the city’s geography—on a wide river delta—was an attractive feature in this regard. The atomic blast—detonated at an altitude of 1,900 feet—could expand over this relatively unimportant city, unimpeded by natural barriers. Military strategists wanted a pristine target to measure the true destructive capabilities of their new weapon, both for their own benefit and as a display of power to their postwar rival, the USSR. A test on a desert island wouldn’t do; they needed to see incontrovertible, measurable damage on an inhabited though previously pristine city.

Residents of Hiroshima invented sadly misguided explanations for why their city was spared the devastation that rained down on so many other cities that summer. They speculated that they were granted mercy since a large portion of the Japanese population in the U.S. had emigrated from Hiroshima. Such explanations speak to the eternal optimism of the human spirit—and a tragically false sense of security. It was not out of any sense of mercy, but in the name of empirical science, that Hiroshima was spared destruction by incendiary or other conventional bombs. As the more pessimistic residents of the city predicted, the U.S. was saving something special for them.

Today, the hypocenter is a narrow street where the reconstructed Shima Hospital stands. A block over is the Hiroshima Peace Park featuring the T-Shaped bridge, the Hiroshima Peace Museum, and, for Americans, the most iconic A-bomb-related image aside from the mushroom cloud itself—the Atomic Bomb Dome, formerly known as the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall. As a concrete structure designed and built by Europeans in 1921, it was one of the few buildings left standing in the otherwise wooden city of Hiroshima. Today, though the city around it is modern steel and glass, it stands in ruins, slightly reinforced but largely in the same apocalyptic condition it was in by the end of the day on August 6, 1945. A lot more grass grows around it these days, underscoring the fact that time has passed and that for many, even in Hiroshima, life goes on.

Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum

The sobering interior of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum stands in stark contrast to the serene 120,000 square meter park surrounding it. Exhibits featuring photos, artifacts, and thorough Japanese and English-language captions guide the visitor through the history of Hiroshima in the late 1800s all the way through the post war years of reconstruction and economic boom.

The first floor of the museum goes to great lengths to demonstrate that Hiroshima had a military past as a staging ground for the army and navy in the late 1800s. However, it is vague about the fact that this was no longer true by the time August 1945 rolled around. The overall effect seems to justify Truman’s specious claim that Hiroshima was a “military base.” In a museum designed to be critical of the atomic bomb, the implication is kind of troubling—this is subtle form of apology, that Hiroshima and its civilian population in some way deserved their fate.

The top floor of the museum is the must-see exhibition. It is the reason this museum packs such an emotional wallop. The bomb detonated at 8:15 am on August 6, 1945, so the exhibit displays watches and clocks—all charred and distended—each frozen exactly at that fateful moment. The story of the bomb’s effect on Hiroshima continues, becoming more intimate and personal. There are display cases full of tattered, singed clothing, much of it from children.

One mother saved the peeled and blistered skin of her only son, killed in the attack, to show to her husband, a soldier, when he returned from the front. This pile of roasted human flesh, brown and leathery with age but still recognizable as human is on display in a glass case near the middle of the exhibit. It is hard to look at these items even in the sterile, secure environment of a museum. It must have been another thing entirely beyond our modest capacity to imagine, seeing these horrors in the original context of that day…

Barefoot Gen

That is why hibakusha Keiji Nakazawa wrote and illustrated the popular manga series Barefoot Gen. This comic book relates a semi-autobiographical account of his experiences as a young boy growing up in Japan during and after the war. Leavened with cartoon humor and touching characterization, its centerpiece is a gruesome depiction of the atomic bomb and its aftermath. He has translated righteous anger into powerful art with a profound message of peace.

We’re meeting in a small conference room in a high-rise office building across the street from Hiroshima city hall. Nakazawa is seated before us at a long conference table. Like most of the aging hibakusha population, Nakazawa’s health is in decline these days. His rare public appearance to meet with my small touring group, arranged through some lucky personal connections, is worthy of television news coverage in Japan. Nakazawa begins his story. Cameras click and film crews jockey for just the right shot. It’s like some surreal world where the sixty-six year old story of the atomic bomb is breaking news.

As he relates the story of what happened to him as a six year-old on August 6, 1945, Nakazawa’s eyes are fixed in the distance. Wherever he is, he is not in this conference room with us. Even as he explains that he survived the bomb blast by sheer luck – the stone wall outside of his school collapsed on him, saving his life. It failed to crush him because it also fell on a tree, which partially propped up the section of the wall next to which he was standing. A grown woman who he had been speaking with at the moment of the blast was instantly charred to death right before him—she happened to be standing not in front of the wall but in front of the schoolyard gate, which offered her no protection. He is distant, even as he describes in lurid detail the sounds of his father and brother’s screams for mercy and help. They burned alive, trapped under the rubble of their own collapsed home while Nakazawa and his mother watched helplessly. Our translator is weeping, sobbing to the point where she needs several moments to compose herself before he can continue his story. But he is impassive, still seemingly a world away.

A lot of hibakusha tell their stories this way, in a droll matter-of-fact tone that belies the urgency of their message. I guess, how could you recount such traumatic events repeatedly over the years without bracing yourself to their emotional effects? Who would want to relive the emotional distress of an atomic bomb blast day in and day out for almost seventy years?

Many Japanese think of the nation’s current constitution—the so-called Peace Constitution with its controversial Article Nine barring an offensive Japanese military—as a foreign document devised by a victorious U.S. intent on keeping its former enemy weak. Not Nakazawa. Perhaps his most profound formulation is this: the Peace Constitution is an opportunity to be embraced, earned by the Japanese people through their sacrifice under a brutal and militaristic government.

Similarly, Nakazawa welcomes the postwar constitution’s freedom of speech guarantee. Such a thing would have kept his pacifist father from suffering physical intimidation and jail time for his public opposition to the war. Reflecting on this, he says, “After the war, we can say what we want. This is democracy. But what have people learned from Hiroshima and Nagasaki?”

He says that he wrote Barefoot Gen to document the unique experience of the hibakusha and to pass the torch of world peace and nuclear abolition on to a younger generation. Turning to the prospect of nuclear abolition, he becomes more animated, speaking with a sudden passion that transcends the language barrier. “What can’t people understand? We are living with the danger of total annihilation… What a stupid thing. We want a world without nuclear weapons, and we hibakusha pass this torch on to you. I am 72. I will die. Go back to the U.S. and tell a lot of people what you learn here.”

I’m trying, Mr. Nakazawa.