By David Feela

By David Feela

A meeting one author will never forget.

A life that gives rise to 51 books in the short span of 79 years can certainly be regarded as literary. William Stafford lived such a life. But Stafford was also a man who refused to occupy a literary pulpit for the sake of preaching to the masses. Stafford’s life stood for a quieter way, a daily ritual of writing that produced not only a legacy of remarkable poems but also a way of thinking about the process that creates poems. James Dickey called William Stafford one of those poets “who pour out rivers of ink, all on good poems.” The poems themselves are often short, focused on simple local details, and unusually accessible, relying on the power of everyday speech to examine the world around the poet. What’s amazing about Stafford’s poems though is that their language is far from ordinary, for he captures the nuances of phrase and image. Recipient of the National Book Award, Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress, professor at Lewis & Clark College, and teacher on the campus known as the earth, Stafford touched as many lives in his travels as he did through his writing.

I had known William Stafford for over twenty years before I met him–known him, that is, in the way any reader comes to know an author, holding his ideas in my hands, believing his physical self somehow incapable of standing beside his work. We were, strangely enough, introduced by a series of coincidences, but it seemed afterward as if some great design in the universe continually suggested that I meet the man behind the writing.

I never vigorously sought Stafford’s counsel through his books, but it didn’t matter: his writing continued to materialize in an astounding number of publications. As a student of poetry in the 1970’s it was impossible to pick up an anthology or little magazine without encountering one of Stafford’s poems. As he told me much later, the best advice he followed was to send more material into the mail than anyone could possibly imagine. He dryly suggested that he’d flooded the market.

Shortly after I moved from Minnesota to teach in Colorado, Stafford surfaced again–this time more noticeably–still in print, but revealing something more of the man behind the poems. I had become in my spare time a thrift store book scout, browsing endless shelves of dusty, abandoned volumes, searching for first editions of literature I could sell to used book dealers. To my surprise I found a thin, prose volume with the name “William E. Stafford” on the cover. The title was Down In My Heart, a book I didn’t recognize, but I bought it for one dollar on the hunch that it might be related to William Stafford, the poet. The year was 1983. To my even greater surprise, Stafford was writing about his commitment to peace as a conscientious objector during World War II; I had recently become a Quaker. Years later Stafford remarked that the edition was probably worth $200.00 but that he (winking) would never pay such a price. He signed it, “William Stafford, April, 1988”–exactly forty years after it had been published as his Master’s thesis.

While completing classes at Fort Lewis College in Durango, Colorado, my wife introduced me to a couple she’d met and fate seemed to take over again. One of them happened to be the son of a man who’d worked with William Stafford in the Forest Service camps during World War II. Generosity led to opportunity. I received word that William Stafford would be reading and conducting a workshop in Cedar City, Utah, so my wife and I rode our motorcycle a long and tedious day for the chance to meet him face to face.

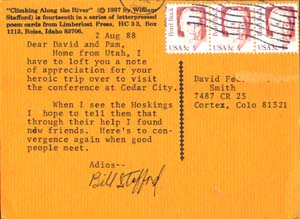

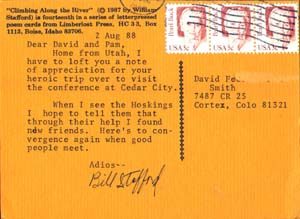

The evening with William Stafford was too short. We left the next morning to get back to work. I probably talked with him no more than a half an hour. He laughed when my wife told him he was my hero and said he’d have to be sure to tell his wife, that she’d be surprised to know her husband inspired such devotion from a couple of strangers who’d suffered a motorcycle for ten hours just to say hello. I told him about my history with his work, the events that led me to find him, and he laughed again, suggesting that he was the one who was lucky to have planned Cedar City into his summer. We talked. I don’t even remember what we could have discussed. It couldn’t have amounted to much and it doesn’t matter now. We shared that moment and somehow he managed to make it seem to mean as much to him as it did to me. I told him, trying my hardest to be literary, that I’d noticed how often he used the word “remember” in his poetry. He said he guessed life was like the tread on a big bulldozer, gripping the dirt from behind and always pulling it forward, packing it, then pulling it forward again. Those were close to his exact words: I wrote them down shortly after we left. It was the only poetry he spoke, the rest had to have been the man himself-not literary personality or smug critic–just plain-spoken William Stafford, more like the “Bill” he fixed to a copy of his poems, Passwords, that our college friends mailed to me as a birthday present four years later–“For David, Remember when we met?”–as if to remind me of an event he treasured, as if I could ever forget.

David Feela’s chapbook, Thought Experiments, was published by Maverick Press as the winner of the Southwest Poets’ Search. He writes and works as a teacher in Cortez, Colorado.

More on the Web

Friends of William Stafford

is a non-profit organization dedicated to raising awareness of poetry and literature worldwide using the legacy, life and works of the late award-winning poet William Stafford.

Originally Published in 2000 on Literary Traveler.